In the annals of mathematical history, few names shine as brightly as Brahmagupta, the 7th-century Indian mathematician and astronomer who revolutionized arithmetic by introducing rules for zero and negative numbers. At a time when most civilizations struggled with abstract concepts like “less than nothing,” Brahmagupta’s insights laid the foundation for modern algebra and computational logic.

Who Was Brahmagupta?

Born in 597 CE in Bhillamala (modern-day Bhinmal, Rajasthan)

Head of the astronomical observatory at Ujjain, a major center of learning

Authored two major works:

Brahmasphutasiddhanta (628 CE) – “The Correctly Established Doctrine of Brahma”

Khandakhadyaka – a practical manual for astronomical calculations

Brahmagupta’s work was composed in Sanskrit verse, blending poetic elegance with mathematical rigor—a hallmark of Indian scholarly tradition.

The Conceptual Leap: Negative Numbers as Debts

Before Brahmagupta, subtraction that resulted in a negative value was considered meaningless. For example, 3 – 4 was either undefined or simply zero. Brahmagupta changed this by introducing the idea of “ऋण” (ṛṇa) or debt to represent negative numbers, and “धन” (dhana) or fortune for positive numbers.

💡 His Framing:

Fortune (धन) = Positive number

Debt (ऋण) = Negative number

Zero (शून्य) = Neutral balance

This metaphorical framing made abstract arithmetic relatable, especially for merchants and accountants in ancient India.

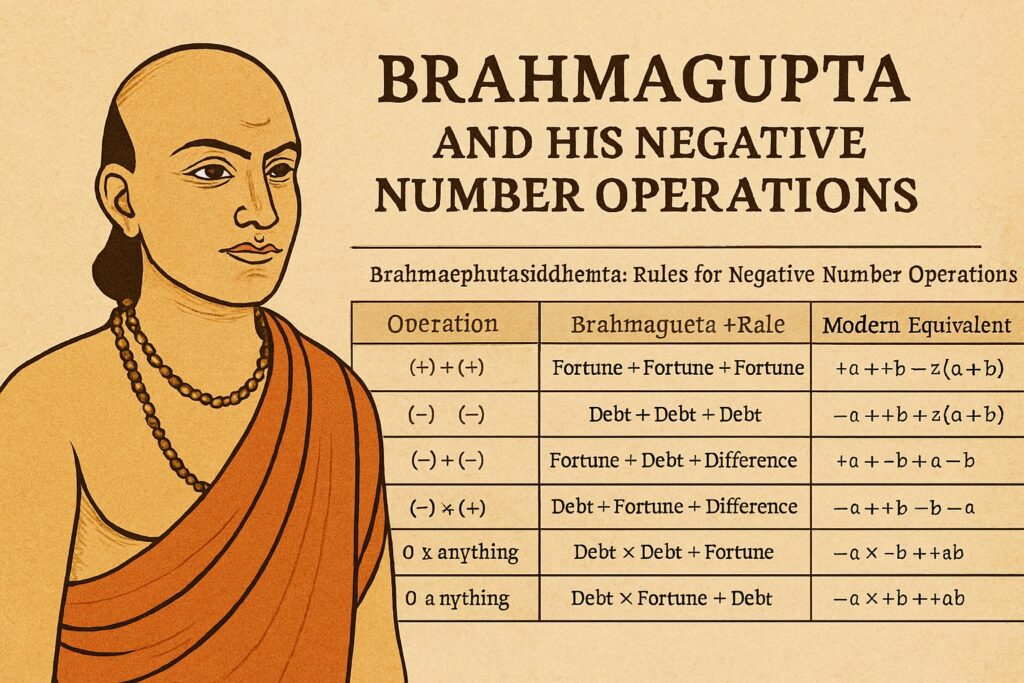

Brahmasphutasiddhanta: Rules for Negative Number Operations

In Chapter 18 of Brahmasphutasiddhanta, Brahmagupta laid out rules that resemble modern algebraic operations. Here’s how he defined them:

| Operation | Brahmagupta’s Rule | Modern Equivalent |

|---|---|---|

| (+) + (+) | Fortune + Fortune = Fortune | +a++b=+(a+b)+a + +b = +(a + b) |

| (–) + (–) | Debt + Debt = Debt | −a+−b=−(a+b)-a + -b = -(a + b) |

| (+) + (–) | Fortune + Debt = Difference | +a+−b=a−b+a + -b = a – b |

| (–) + (+) | Debt + Fortune = Difference | −a++b=b−a-a + +b = b – a |

| (–) × (–) | Debt × Debt = Fortune | −a×−b=+ab-a \times -b = +ab |

| (–) × (+) | Debt × Fortune = Debt | −a×+b=−ab-a \times +b = -ab |

| 0 × anything | Zero × any number = Zero | 0×a=00 \times a = 0 |

These rules were centuries ahead of their time. Europe, for instance, didn’t fully embrace negative numbers until the 16th–17th centuries.

Zero and Division: A Mixed Understanding

Brahmagupta also tackled operations involving zero, a concept he helped formalize:

Addition/Subtraction with Zero: Leaves the number unchanged

Multiplication with Zero: Always yields zero

Division by Zero: He proposed that a÷0=0a ÷ 0 = 0, which is mathematically incorrect but shows his attempt to grapple with the concept

Despite this flaw, his work on zero was foundational and influenced later scholars across India and the Islamic world.

Global Influence and Transmission

Brahmagupta’s work didn’t remain confined to India. Through translations like the Sindhind (Arabic version of Brahmasphutasiddhanta), his ideas reached:

Islamic mathematicians like Al-Khwarizmi and Al-Biruni

European scholars during the Renaissance

Modern algebraic systems, which still use his sign rules

His legacy is a testament to India’s early comfort with abstraction, symbolism, and conceptual mathematics.

Cultural and Philosophical Resonance

Brahmagupta’s framing of numbers wasn’t just mathematical—it was philosophical:

Debt and fortune mirror karma and dharma, central themes in Indian thought

Zero represents śūnyatā, or emptiness—a concept revered in Buddhist and Hindu metaphysics

His work reflects a holistic worldview, where mathematics, astronomy, and philosophy are intertwined

This cultural depth makes Brahmagupta not just a mathematician, but a civilizational thinker.

Brahmagupta’s contribution to mathematics is nothing short of revolutionary. By introducing negative numbers, formalizing zero, and crafting rules for arithmetic operations, he laid the groundwork for modern algebra and computational logic.

His legacy reminds us that mathematics is not just numbers—it’s a reflection of how civilizations think, trade, and philosophize. In Brahmagupta’s world, even a debt had meaning, and even zero had power.